To call it the ‘Lake District’ is a bit of misnomer for

although there are ninety four designated bodies of water within this region of

north west England, only one of them, Bassenthwaite, is officially a lake. All of the others are Waters, Meres, Tarns, with

a couple of reservoirs thrown in for good luck.

As if anyone really cares about the titles. Arthur Ransome was not pedantic in such

matters. Early in his autobiography he

talked about sharing his father’s “passion

for the hills and lakes of Furness” and “Lake

Country holidays.” (Actually his

description of his father was delightful.

“Every long vacation he was no

longer a professor who fished, but a fisherman who wrote history books in his

spare time.”) But I digress.

It was to Coniston Water that I was heading that morning,

winding my way down the lanes, emerging at Lowick Bridge and taking the narrow

road than ran with passing places along the River Crake and then up the east

side of the lake. Annoyingly enough I

could not see the water at first except for the occasional glimpse between

private houses, but after a couple of miles the scenery opened out and Coniston

appeared, blue-grey and choppy in the morning’s north wind. I had read that there was a National Trust

parking area - one that held only three cars – and I simply prayed that there

was space for my small car. There was!

The eleven acres of shoreline at Low Peel are a pleasant

enough walk in themselves but it was not woodland which was drawing me – it was

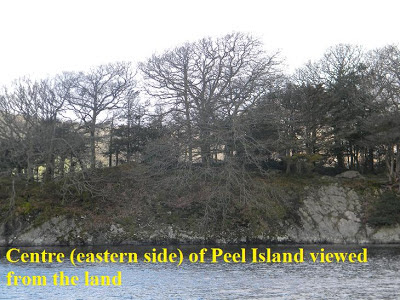

what may be seen at the northern edge of the trees. There, a mere three hundred feet into the

lake was Peel Island. All of a sudden I

had re-entered not only my childhood imagination as a reader but also connected

with Ransome’s own memories. He wrote of

his experience staying with the Collingwood family in 1904, aged twenty:

I was bidden to

come early next morning and ‘my aunt’ packed us off with a bun-loaf, a pot of

marmalade and a kettle to go down the lake to Peel Island, the island that had

mattered so much to me as a small boy, was in the distant future to play its

parts in some of my books, and is still, in my old age, a crystallising point

for happy memories. (The

Autobiography. 1976.)

But Ransome had inherited a fascination for Peel Island

from his adopted uncle, William Collingwood, who in 1895 had written a

children’s novel about Norsemen in 10th century Cumbria. Thorstein

of the Mere introduced Peel Island with a pen and ink map and these words:

In the midst of Thurston-water there

is a little island, lying all alone. When you see it from the fells, it looks

like a ship in the blue ripples; but a ship at anchor, while all the mere moves

upbank or downbank, as the wind may be. The little island is ship-like also

because its shape is long, and its sides are steep, with no flat and shelving

shores; but a high short nab there is to the northward, for a prow, so to

speak; and a high sharp ness to the southward, for a poop. And to make the

likeness better still, a long narrow calf-rock lies in the water, as if it were

the cockboat at the stern; while tall trees stand for mast and sails.

The island is not so far in the water but that one can swim to shore,

nor so near that it would be easy to attack it without a boat: and at that time

boats there were none on these lakes, except maybe a coracle or two of the

fell-folk. For fishing, no spot could be better, nor for hunting, if one wanted

a safe home and hunting-tower.

(Thorstein of the Mere. P 261)

And, of course, in 1930, came the lines familiar to

children of all ages for generations to come:

The island was not

in the middle of the lake but much nearer to the eastern shore… covered with

trees and among them was one tall pine which stood out high above the oaks,

hazels, beeches and rowans…. The tall pine was near the north end of the

island. Below it was a little cliff

dropping to the water. Rocks showed a

few yards out from the shore. There was

no place to land there…. A little more than a third of the way along the

eastern shore of the island there was a bay, a very small one, with a pebbly

beach… The only place where it would be possible to land a boat.

But later Captain John, exploring on foot, found the

hidden harbour on the south west corner of the island.

Beyond it… ran out nearly

twenty yards into the water, a narrow rock seven or eight feet high, rising

higher and then dropping gradually. Rocks

sheltered it also from the southeast.

(Swallows and Amazons chapters 3 and 4.)

In the books where the Swallows and the Amazons sail the

lake, unnamed except for in their imaginations, is an amalgam of Coniston Water

and Windermere, but there is no doubt whatsoever that Peel Island was the

prototype for Wild Cat Island. (Except the eastern "landing place" is a bit of an exaggeration.) Looking

at it from under the shoreline trees I felt a childish sense of

excitement. And that day I had the view

all to myself, for I knew that on brighter, warmer days, the waters around the

island are full of small boats and other craft with people enjoying themselves,

perhaps pretending that they were the Walker or the Blackett family, or just

telling their young children about books that they had read growing up.

It was eventually time to go. Walking back to the car I took a last look at

the island. “What a place!” said the able-seaman. And it was, but the day was marching on. My

plan was to eat an early lunch in Coniston village and wander around lazily for

a while. Little did I know that I would

soon abandon those ideas and be afloat.

(*) The title of Swallows and Amazons Chapter III

(*) The title of Swallows and Amazons Chapter III

.JPG)

.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment